GAZE

Intimate Encounters with Photography

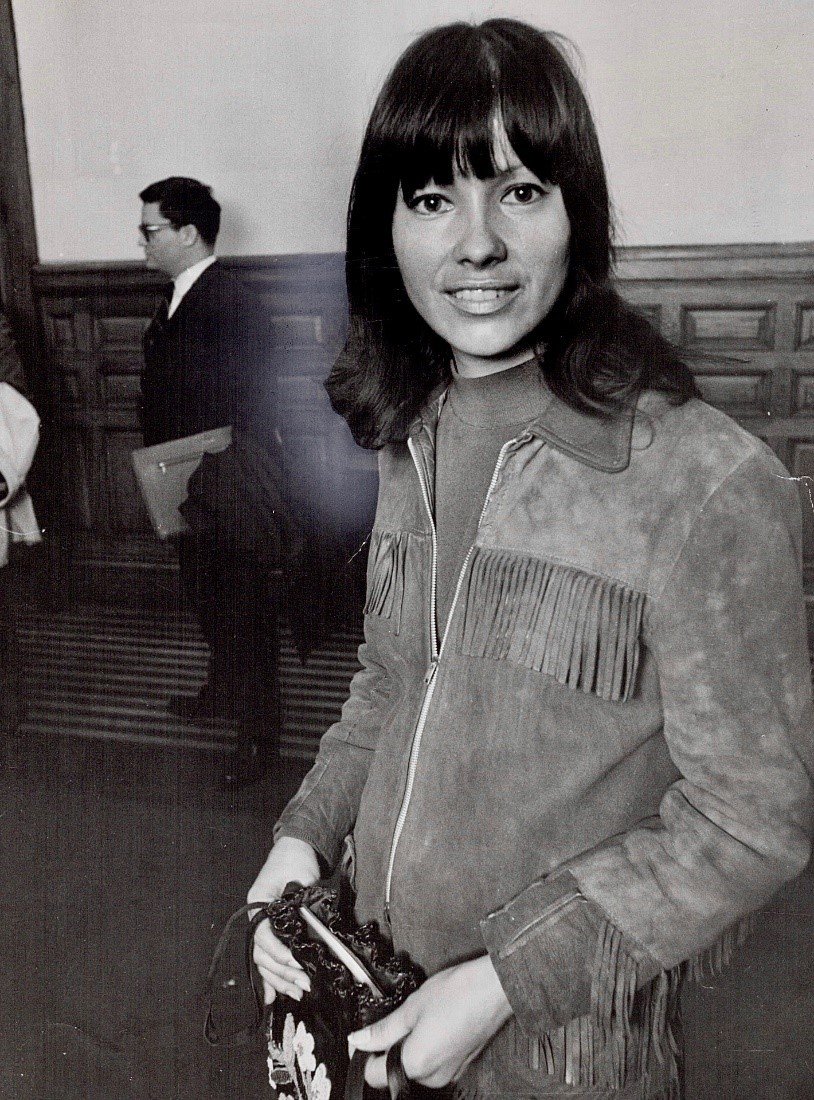

Kahn-Tineta Horn waiting to speak. Photo: Bob Whyte. Event and locale unknown. 1969 [Toronto Star Archives/Toronto Reference Library].

Kahn-Tineta Horn at an event, likely Toronto. Photo: Bob Olsen. 1968 [Toronto Star Archives/ Toronto Reference Library]

by Paul Seesequasis

EXCERPT

Kahn-Tineta Horn has been many things in her life: a wife, a mother, a student, a secretary, an Indian Princess, a tourist, a model, a spokesperson, a civil servant, an activist. The variety inherent in her lived experience is also reflected in the many photographs taken of her. Because she had been a model (Photo #7), she was at ease with the camera’s relentless gaze. If one accepts the view that Susan Sontag put forth in On Photography that with the camera “no reality is exempt from appropriation” and in a world ruled by the image “all borders (‘framing’) seems arbitrary” then the many photos of Horn, one of the most photographed Indigenous women of the 1960s and 70s, represent colonial fascination, an extension of the dominant culture’s desire to contain—to exoticize, romanticize, and also pity the Indian. But Horn was raised as a proud Kanien’kehá:ka woman from a strong family and as she matured, this pride and strength only grew stronger, more resilient, more likely to transcend the possessiveness of the camera.

Photography is considered informative, a snapshot of reality, but it is also equally capable of lying, of distorting that reality, of creating a false truth. Horn was, as an object of the photographic gaze, very much a manifestation of a false truth. She is undeniably photogenic; this fact was in play long before she became a celebrity, and she is Other, Kanien’kehá:ka; not only Indigenous but Mohawk Indigenous, with all the weight that that name carries historically and conjures in the modern colonial mind. It is a false truth also in that her photographic image is not captured fully by the early 1960s societal gaze, which sees a beauty, and an Other; the assumptions likely drawn from that framing are inherently wrong. The subject here is aware of what she is doing; she is consciously using her self-image to reframe the photo, to turn the focus on herself into a political act. Her passion, regardless of the photographer's intent, is focused on change, not on the stillness of a singular moment in time. She is in motion; the photograph is not.

…

Journalist Peter Gzowski wrote in a May 1964 edition of Maclean’s magazine that Horn was “not a ‘typical’ Indian…. For all her charm, and her girlish enjoyment of being something of a celebrity, she can often turn on a calculated flattery that is too obviously calculated.” He was alluding, unconsciously perhaps, to the threat underneath the veneer of beauty. The settler gaze, in the 1960s, had many ‘typical’ images of Indian reality; often these included poverty, despair, and poor living conditions. Horn was decidedly not this type of Indian but she spoke of it, pointing a metaphorical finger at the photographer and, subsequently, at all those gazing at her image.

Gzowki wrestles with this in his two-part Maclean’s feature. Addressing her modeling career, he writes, “She could pose as anything from a Spanish dancer to an Indian maiden…. She has, of course, missed out on jobs because she looks exotic.” He segues into how her looks afford her an audiences for her political views: “She has won an audience for her ideas about Indian nationalism,” which Gzowski judges are still forming and are “often misinformed.” He acknowledges that she was most reluctant to talk about herself and wanted to focus on issues, whereas, as the article makes clear, he wanted to talk about her. This tug-of-war between the passion that drives Horn, which is a collective passion—a desire to advance Indigenous rights and conditions—and the colonial pressure to focus on the individual—on her—in order to consume and possess her, was a long-standing battle in Horn’s life.